Comparing the impact of wind turbines with other contributors to contributors to bird and bat mortality

One of the main environmental concerns associated with wind energy is bird and bat collisions with wind turbines. Studies report that wind turbines kill 4-11 birds and 12-19 bats per megawatt capacity per year in the United States. The US currently has approximately 145 GW of wind capacity, and applying those mortality rates to this capacity results in an estimated 0.6-1.5 million birds and 1.7-2.8 million bats killed at wind facilities every year. These are very rough estimates since mortality rates vary substantially by geographic area, species, and facility design.

These impacts are not insignificant, but they need to be considered in context rather than in a vacuum. For starters, the impact of wind turbines on birds and bats should be evaluated against the impact of current fossil fuel-based energy production. Fossil fuel use drives climate change which is a leading threat to both birds and bats. One analysis estimated fossil fuel facilities in the United States cause 14.5 million avian deaths per year, including both direct mortalities and indirect mortalities related to climate change.

Wind farms help to mitigate climate change by displacing energy production from fossil fuel power plants that emit pollutants and contribute to climate change. Indeed, given the threat climate change poses to birds and bats, conservation groups like the Audubon Society are supportive of appropriately sited and designed renewable energy projects that will help mitigate climate change. Despite direct mortality from wind infrastructure, clean energy development has a net positive impact on wildlife.

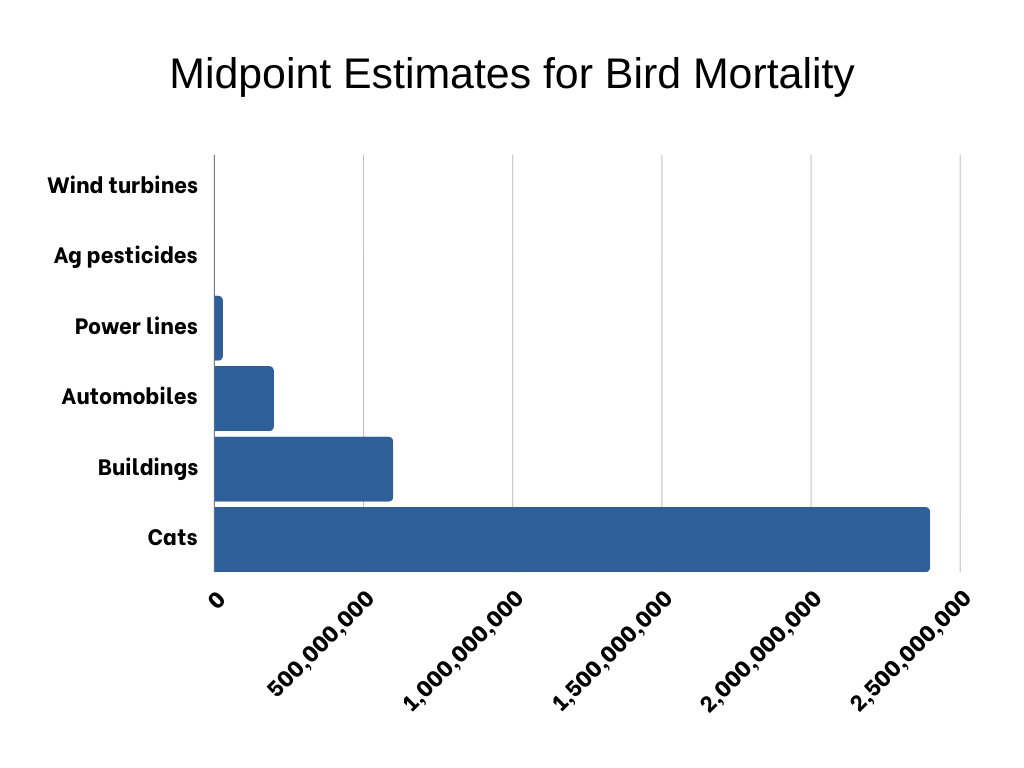

As a society, we tolerate significantly larger contributors to bird mortality that offer no clear benefit to wildlife: collisions with buildings kill about 600 million birds per year, vehicle collisions kill over 200 million birds every year, and outdoor cats kill a staggering 2.4 billion birds per year in the United States, 70% of which come from unowned or feral cats.

Responsible site selection for wind development can help to reduce impacts by avoiding high quality habitat areas—particularly for state– or federally-listed species—and avoiding migration pathways or other high concentration areas.

Curtailment—stopping blade rotation at lower wind speeds when bats and birds are most active—has been shown to reduce bat mortality by 30-85%. Of course, curtailment comes at the expense of energy production so an appropriate balance must be achieved. There are different curtailment methods to maintain a balance of energy production and wildlife protection. Blanket curtailment refers to universally delaying the wind speed at which the turbine blades begin to engage from the typical 6-9 mph until a higher wind speed, such as 10-15 mph. Blanket curtailment can be implemented during certain times of the year when bats are most active such as mid-summer through the fall migration. Smart curtailment uses information about wind speed and local bat activity to more selectively power down the wind turbines and reduce unnecessary loss of electricity generation.

Some acoustic and visual deterrents have also been shown to significantly reduce bird mortality. For example, painting one turbine blade black to make the rotating blades more visible reduced bird mortality by 70% in one study.

While these are good advances, more work still needs to be done to better understand what factors contribute to collisions and how best to minimize them. In 2021 Federal infrastructure law included $7.5 million dollars to the Department of Energy to fund research to help fill these knowledge gaps and test new methods of mortality avoidance.

Hopefully this research will yield useful insights to guide future wind farm siting, design, and operation and further reduce bird and bat collisions while generating the clean energy that is needed to combat the massive threat to biodiversity posed by climate change.