By Meghan Parmentier, Summer Research Intern

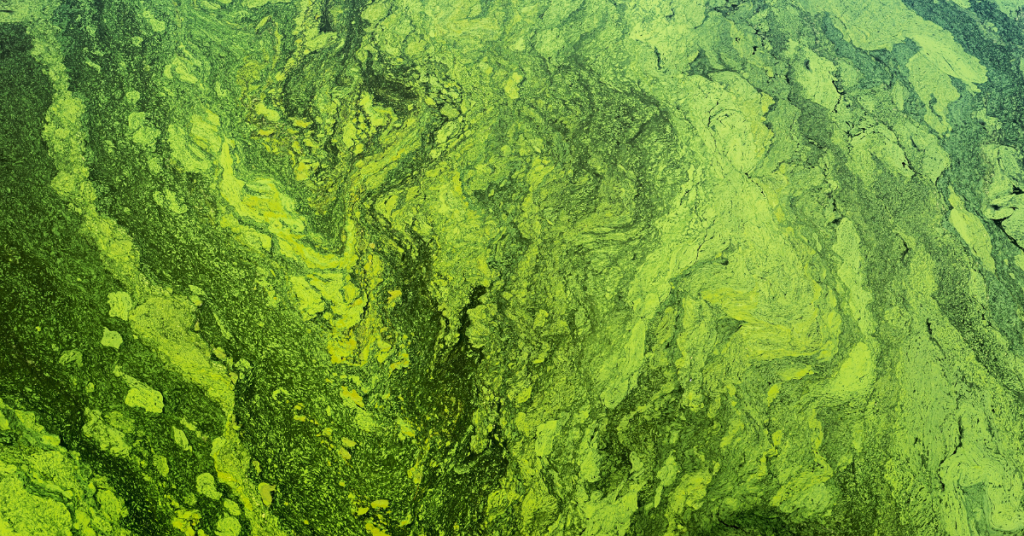

Summertime in Wisconsin often comes with algal blooms, some of which can pose risks to people and pets spending time in the water. Here we look at algal blooms, the risks they pose, and what to watch out for and avoid.

First off, it is important to understand the difference between true algae and cyanobacteria. Algae are found in every river, pond, and lake in Wisconsin, and they are essential for the growth and survival of aquatic ecosystems and humans on Earth. Like plants, algae take in carbon dioxide from our atmosphere and release oxygen. As primary producers, algae are essential to food webs because they are eaten by zooplankton, insects, snails, and other microorganisms. Algae require nitrogen and phosphorus for growth, so their abundance is limited by the amount of these nutrients in the water. When there is an excess of nutrients — the chemicals that algae need to thrive — it can grow rapidly, a process known as a “bloom”. However, while excessive algae growth can be a nuisance, algae do not produce harmful toxins for humans or animals.

Cyanobacteria, on the other hand, are bacteria that can produce toxins that are harmful for humans and animals when they grow into cyanobacterial blooms (cyanoHABs). Cyanobacteria are commonly confused with true algae (and are sometimes referred to as blue-green algae) because of their similar appearance. Like algae, cyanobacteria undergo photosynthesis and exist in every aquatic ecosystem in Wisconsin. However, cyanobacteria can produce toxins and are generally not eaten by other aquatic organisms. Cyanobacteria also thrive in nutrient-rich water and are typically found in warmer bodies of water.

In Wisconsin, human activity has resulted in higher levels of chemicals like nitrogen and phosphorus entering aquatic ecosystems, and climate change has created better conditions for cyanobacterial growth. Nutrient pollution in aquatic ecosystems is largely driven by runoff from industrialized agriculture, discharges from wastewater treatment plants, and urban runoff including home lawn fertilizers. Wisconsin has also lost half of its original wetland acreage, which has made it difficult for aquatic ecosystems to filter and cycle out excessive agricultural runoff. Climate change has exacerbated cyanobacterial growth in Wisconsin because warmer and wetter seasons are extended and more extreme; therefore, blooms can occur rapidly and sustain throughout the humid summer seasons.

CyanoHABs can produce “cyanotoxins” of various forms that are harmful to humans and animals. When interacting with water that is contaminated with cyanotoxins, people can be exposed by drinking the water, inhaling water spray from water-related recreational activities, direct skin and eye contact, eating contaminated fish, and by drinking illtreated tap water during an extreme bloom event.

The most common toxin found in Wisconsin is microcystin-LR, which can cause various health symptoms like liver disease, abdominal pain, headache, sore throat, nausea, dry cough, diarrhea, blistering around the mouth, pneumonia, and acute hepatitis. These symptoms vary depending on the person’s pre-existing conditions, how they were exposed, and how much cyanotoxins they were exposed to. Those who have pre-existing liver conditions, colon disease, asthma, and skin diseases should take extra precautions before swimming in water with potential harmful algal blooms this summer.

Nationally, harmful algal blooms are estimated to cause $20 million in health care costs each year. Here in Wisconsin, the Department of Health has confirmed 99 harmful algal bloom-related illness cases since 2016, with between 4 and 25 reported every year. However, this likely underestimates the true number of cyanoHAB illnesses since the most common cases include more mild symptoms like diarrhea and fever, which tend to resolve themselves and never get reported.

Boiling water that is contaminated with cyanotoxins is ineffective and not recommended because the high temperature further activates the toxins in the water. When mitigating surface blooms, avoid using chemical treatments because they exacerbate the concentration of toxins in the bloom. The best practice to prevent exposure is to avoid swimming in water that has an unusual blue-green hue, small green dots floating in it, looks like spilled latex paint, has a rotten egg smell, or a pea soup appearance. When in doubt it is best to stay out!

For most people in Wisconsin, it is unlikely for their drinking water to be contaminated by cyanotoxins. All private wells and many public water systems get their water from groundwater, which is not subject to cyanoHABs. Of those systems that get their water from surface water, most get it from intake pipes extending far enough, and deep enough, offshore in Lake Michigan or Superior that cyanoHABs are unlikely to contaminate the water because most blooms occur on the surface of the shallow-most part of the lake.

However, there is the potential for shallow surface water sources like Lake Winnebago to become contaminated from extreme bloom events. While most public water treatment processes can filter typical levels of cyanotoxins from their intake site, these mechanisms can be overwhelmed when the concentration of cyanotoxin is too high. For example, in August 2014 cities that used drinking water from the western basin of Lake Erie were placed under a “do not drink” notice for several days due to concentrations of microcystin-LR over safe levels.

Dogs are very susceptible to cyanotoxin poisoning because they tend to swallow contaminated water very quickly, they cannot tell whether the water is contaminated or not, and they have smaller bodies so smaller amounts of water can make them sick faster. Be sure to clean yourself and your dog immediately after swimming to reduce exposure, but if you notice your dog is exhibiting unusual behavior like vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, seizures, or extreme fatigue take them to a veterinarian immediately.

Numerous runoff reduction efforts exist statewide, aimed at reducing excess nitrogen and phosphorus from flowing into lakes and rivers. These efforts are critical to keeping HABs under control. Wisconsin also requires healthcare providers to report suspected cyanobacteria poisoning to DHS as of 2018. This, along with improved HAB monitoring and reporting, will help to better understand the scope and extent of HABs in the state. Finally, it would be beneficial for cyanotoxins to be listed as a drinking water contaminant under the Safe Drinking Water Act and be regulated federally. This would in turn require public water systems to monitor concentrations and be better prepared for extreme bloom events.