Pesticides are widely used in Wisconsin to control weeds and pests that threaten crop yields. Properly used, pesticides play an important role in increasing crop yields and reducing food spoilage. However, while they play a vital role in agriculture, their use comes with health, environmental, and ecological concerns. Once in the environment, pesticides and their breakdown products can persist for years, spreading beyond their intended targets through runoff and drift. This can harm non-target organisms such as pollinators and can affect the health of residents far from the original application area.

Human health risks most commonly reported from exposure to agricultural pesticides include including damage to the nervous, endocrine (hormone), and reproductive systems, adverse birth outcomes like low birthweight or birth defects, and increased cancer risk.

Two recent analyses have examined the relationship between agricultural pesticide exposure and cancer. One study conducted a comprehensive analysis using county-level data on 69 pesticides to assess the effect of pesticide use patterns on cancer rates. Their findings showed that pesticide exposure was associated with increased cases of leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, bladder, colon, lung, and pancreatic cancer. Another literature review found that the strongest evidence exists for a causal relationship between pesticide exposure and both acute myeloid leukemia and colorectal cancer.

In a previous Defender issue, we looked at neonicotinoid pesticides and here we look at drinking water contamination of non-neonicotinoid pesticides to see how widespread this issue is in Wisconsin.

Looking first at private well contamination, based on sampling by the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP), an estimated 43% of private wells across Wisconsin contain detectable levels of at least one pesticide or its breakdown products. In agricultural areas, the detection rates are above 60%. Atrazine, alachlor, metolachlor, and acetochlor are the most frequently occurring pesticides, all being detected in at least 10% of tested wells.

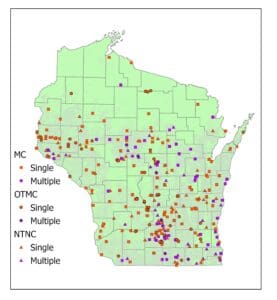

Turning to public systems, 169 water systems serving water to cities, towns and villages in Wisconsin (collectively referred to as “municipal community systems”) had detectable levels of pesticides in their drinking water between 2015 and 2024. Of these systems, 53 had detections of more than one pesticide.

Another 56 systems serving housing developments, condominiums, and mobile homes (collectively referred to as “other-than-municipal community systems”) and 99 systems serving factories, offices, schools, and hospitals (collectively referred to as “non-transient, non-community systems”) had pesticide detections.

As expected, these systems are found in areas with more agricultural land use (Fig. 1).

Atrazine (including its breakdown products) was by far the most commonly detected pesticide, being detected in over 200 different systems statewide, including 127 municipal community systems. The other most commonly detected pesticides include metolachlor (63 systems), dicamba (20 systems), bromomethanes (50 systems), 1,3-dichloropropene (22 systems), pentachlorophenol (11 systems) and alachlor (8 systems).

While detections of pesticides are not uncommon, none of the detections in the datasets summarized here exceed any established drinking water or groundwater standards. This is good news.

However, these standards are established for each pesticide alone. There is evidence that mixtures of pesticides or combinations of pesticides and nitrate, another common drinking water contaminant in Wisconsin, may have harmful effects at lower levels than a single pesticide.

Until we better understand the risks of such cumulative exposure, we need to continue to work to ensure that no one in Wisconsin is drinking water tainted with any pesticides.